When Brahm Erdmann received a random email from a Harvard recruiter in 2020, he’d already quit rowing. The Westlake Boys High School graduate was enrolled to study architecture in Canada and had effectively closed that chapter of his life.

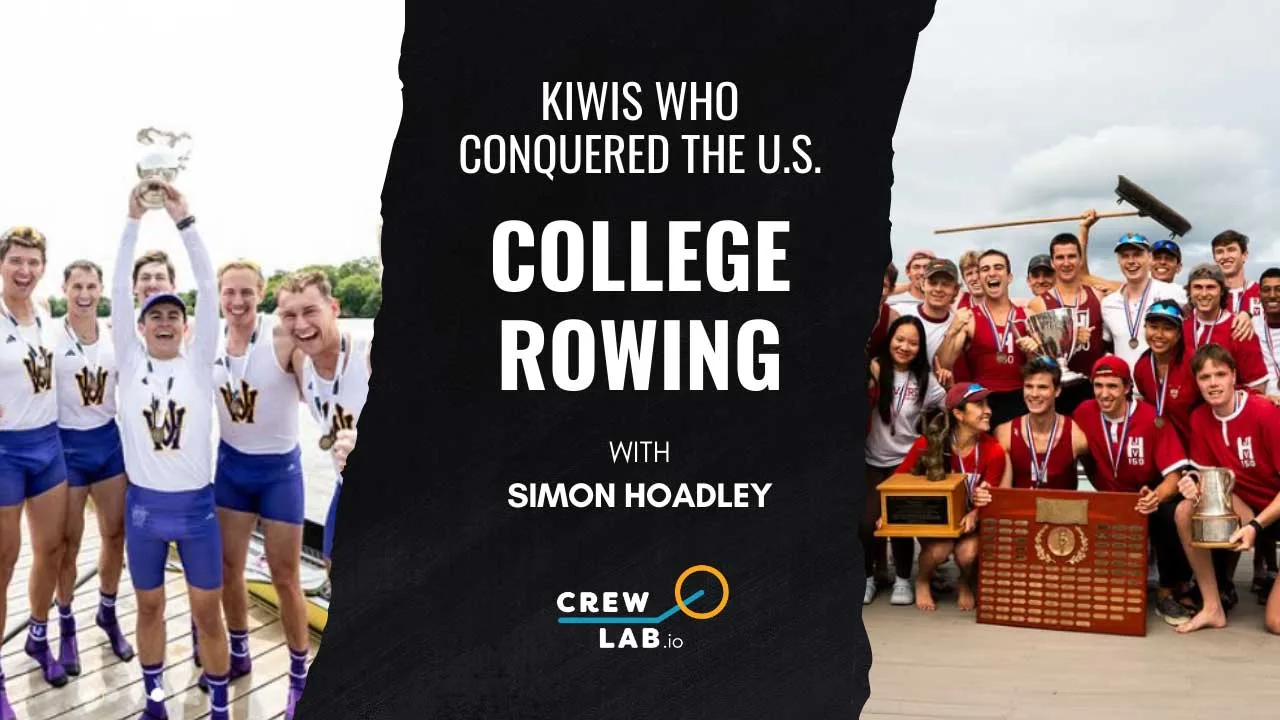

Fast forward to 2025, and Erdmann just finished his second consecutive undefeated season as captain of Harvard’s lightweight rowing team, sweeping every event they entered at the IRA national championships.

On the other side of the country, Kieran from Hamilton, New Zealand never planned to cox either. A deputy principal pulled him aside as a year nine student weighing just 32 kilograms and told him he had to try it. Four years later, he’s led the University of Washington men’s rowing team to back-to-back IRA titles with an undefeated streak stretching nearly two years.

These parallel journeys from New Zealand high schools to dominating the US college rowing scene reveal something interesting about what actually makes teams win.

The secret isn’t the equipment

The first thing that struck both athletes when they arrived in the US was the resources. Erdmann describes rowing out of shipping containers with tarps at Westlake and an aluminum shed at North Shore. Walking into Harvard’s historic Newell Boathouse with “yellow boats everywhere” was a shock.

But here’s what matters: Harvard had yellow boats when they were bad and yellow boats when they were good.

“I feel like everyone loves the hype,” Kieran explains. “Everyone loves all the little crazy things that go on. And it’s like, what’s gonna make me win? What’s gonna make me win? And it’s like, at the end of the day, it’s pretty plain and simple. You do the work. And if you work harder than most other people, you’re probably gonna win.”

This philosophy sounds almost too simple. In an era obsessed with marginal gains and technological advantages, both athletes credit their success to something far more fundamental.

Culture trumps training plans

When Erdmann arrived at Harvard, the team didn’t even qualify for IRAs his freshman year. The talent was there, but something was broken.

“There was so much going on. So many people had their own opinions on what to do. The coaches, the leadership, the athletes—none of them were connected in any kind of way,” he recalls. “Everybody wanted to win really bad, but everybody had their own ideas of what it took to win.”

The turnaround came when the team got smaller, not bigger. After enacting basic standards, roughly 50% of the roster left. What remained was a tiny team that seemed to have lost talent on paper.

But they had something more valuable: alignment.

“The process is so cut clear for us now,” Erdmann explains. “Sessions are very simple. The coach doesn’t really say much at all. It’s pretty quiet out there. You just get things done.”

Kieran experienced a similar evolution at Washington. “Getting people unified and being on the same page has been the main factor. That’s one underrated thing—that’s a big difference between success in a single or a pair compared to success in an eight. So much is just down to how you can have nine people thinking the exact same thing at the same time.”

The crossroads moment

For Harvard, the turning point came with new leadership under captain Greg Kane, who brought a singular focus on hard work over outcomes.

“We kind of trashed the idea of caring about how well we do, caring about the outcomes and more just like showing up and just putting in more than you ever have,” Erdmann remembers. “We became fully process oriented. That was probably the most fun year I had rowing, because it was the least pressure I ever had.”

That year, they finished second at nationals—shocking everyone.

The following season, they could finally set explicit goals. “We want to win the IRA. We want to go undefeated. These were things you earn as you become a better team. But back then, we did not have the right to say any of that kind of stuff.”

What actually works

Both athletes describe a sport that becomes simpler as teams get better, not more complex.

“Growing is a pretty simple sport if you think about it,” Kieran points out. “You go from point A to point B as fast as possible. Like how hard can it actually be?”

This echoes a famous interview with the O’Donovan brothers at a World Rowing Championships, when asked about their race plan: “Oh, there’s no race plan. It’s just start to finish as fast as possible.”

The complexity comes from execution, not strategy. And execution depends on everyone being on the same page.

“If you show up to the start line and you know the guy behind me, the guy in front of me—they’re gonna think the exact same thing as me, they want this just as bad, they are gonna do the exact same thing and commit to moves when I’m committing to them—you have a lot more confidence,” Kieran explains.

The Kiwi factor

Nearly 200 New Zealanders now row in US colleges—roughly 50% of all Kiwis who continue rowing after high school. Coaches consistently cite their work ethic and team-first mentality.

“Maybe as New Zealanders, I feel like we’re pretty good at just getting on with the work and just getting it done. No questions asked,” Kieran reflects. “We don’t need it to be fancy. We don’t need it to be over the top.”

This tall poppy syndrome—the cultural tendency to avoid standing out—actually becomes a competitive advantage in team boats.

“There’s so much to be said for just having the time of day for anyone,” Kieran continues. “Our team is just about upward pressure. Every single person on the team helps the team win. It does not matter if you are the bottom dude on some erg test or the bottom dude on some peer trial. Everyone pushes everyone to be a tiny, tiny little bit better.”

Lessons for any team

The principles that drove these championship teams apply beyond rowing:

Get aligned first, optimize second. No amount of resources or talent matters if everyone has different ideas about how to win.

Addition by subtraction works. Sometimes getting the right people off the team matters more than getting new people on it.

Process before outcomes. Teams that aren’t ready to talk about winning should focus entirely on work quality.

Simplicity scales. The better your team gets, the simpler your approach should become.

Culture is communication. Erdmann describes sessions where “the coach doesn’t really say much at all.” When everyone knows the plan and buys in, words become unnecessary.

The future

Both athletes are now facing decisions about continuing in the sport. Erdmann heads to Henley and considers a national team path. Kieran looks toward coaching, already seeing the value in helping others succeed.

But their immediate advice for young Kiwis considering the US college path? Do it.

“Best decision of my life, 100%,” Kieran says. “You can do it with rowing, go have a good time, get a university degree, meet some really awesome people.”

The pipeline continues. More Kiwis arrive each year, bringing with them a simple approach: show up, do the work, help your teammates, win together.

As for those undefeated streaks? They started when the teams stopped talking about winning and started focusing on how they worked. The medals followed.

Sometimes the most sophisticated strategy is having no strategy at all—just everyone pulling in the same direction, as hard as they can, from start to finish.

Listen to the full conversation

Want to hear more from Brahm and Kieran? Listen to the complete podcast episode where they dive deeper into their journeys, share stories from the boathouse, and discuss everything from making weight as a lightweight to the tradition of racing for shirts.

Listen now on:

Don’t forget to subscribe so you never miss an episode featuring the world’s top rowing coaches, athletes, and sports performance experts.